This episode describes two different perceived risk issues that someone with ND, specifically autism, might deal with:

- The perceived risk of doing anything that is not inertia

- The risk of doing something incorrectly and then having to unlearn poor

Transcript

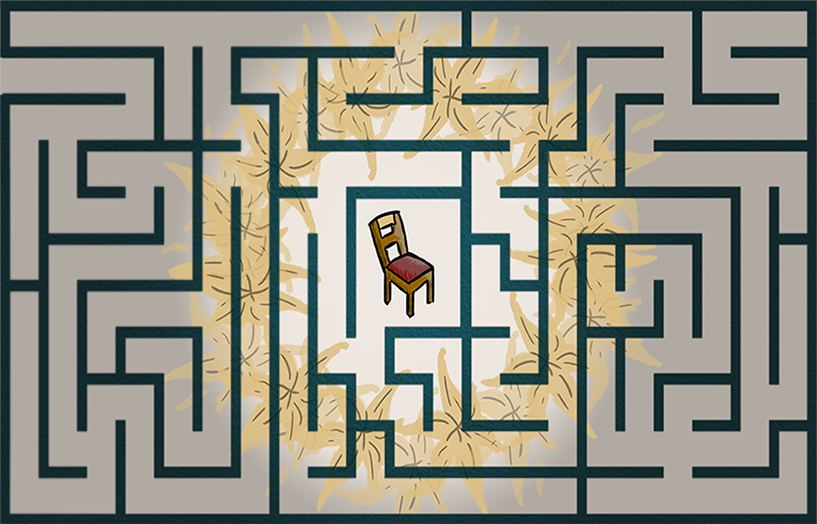

Okay, today we’re going to talk about ‘Risk Bubbles’, which is what I call this difficulty with dealing with risky situations in both a macro and a micro level. And, I think this is unique to my kind of neurodivergence, I think my son has ADHD, and he is all about risk. He’s all about trying things with his hands, and not really listening to what experts say about the best way to get stuff done.But for me, risk is a huge part of everything I do, and it’s like- it’s like a cage. It really is.

I’m Lya Batlle-Rafferty, and this is Memoirs of a Neurodivergent Latina.

__Intro music plays__

I wanna start with macro level things, and then I will go on and talk about micro level things.

So what do I mean by ‘risk’? At the highest level, if you have a neurodivergence like me, you think of everything in terms of risk, even if you’re not consciously doing so. So, when I talk about ‘macro level’ risk, I think of everything around me as kind of this big risk bubble, that I have to push out and push out and push out, and then something sets me back and the risk bubble shrinks again.

So, a really extreme example of that was during COVID. During COVID, we didn’t go out, we didn’t go anywhere. We didn’t get in our cars, we didn’t meet up with friends, and what happened for me is suddenly, my risk bubble became my house. So driving into work seemed huge, like ‘Oh my god, I’m gonna get in a car, and it’s gonna take forever, and it’s so difficult, and I really don’t wanna do it.’ Or meeting a friend for coffee, this was a huge one for me. The first time that a friend invited me to go out for coffee with them, and it was right after COVID, and my first thought was to say ‘No.’ It felt fraught, it felt- I don’t know if dangerous is quite the word, but yeah, something like that. And I actually had to talk to my therapist at the time, who was like: ‘Well, what’s the worst that could happen if you go out for coffee with your friend and you’re careful?” And I said yes! And we went out for coffee, and of course everything was perfect, y’know?

Other ways that this ‘macro risk bubble’ affects me is when I am told that I need to do something that I haven’t prepared for. Usually, for me, it’s in terms of movement, right? So, in terms of going places. I am not typical, in the sense of ‘I like adventure’, ‘I like weird things’, and I consider a schedule a lot like a cage, which is funny, I know. A lot of people who are autistic have like, this- this kind of love of schedules, but for me, schedules cause me a lot of anxiety, and I’ll talk about that in another episode. But the point is: I am not typical in terms of whether or not I want to take risks. However, I have to fight myself to do that.

So, in this example, I was, I don’t know, it was college, and in college I had this great archeology class. It was amazing, I love archeology. And I was in a team- in a group with a friend of mine, who I won’t name, who is probably still pissed with me, or maybe doesn’t even remember it, but was pissed with me back then, because we were supposed to go to this library in this small museum that I had never been to. I’d never been to that part of Boston. I’d never been to that particular museum. I didn’t know how to get around. I was- terrified isn’t quite the word, but it’s probably close. I was very hesitant to go there, and I would find reasons to not go there, and it was especially telling, because I love archeology. I love everything to do with human culture, but I couldn’t get myself to walk out of my room, to walk out of my house, and to go to this unknown place, and take these unknown routes, and get to this unknown library where I didn’t know who to contact to get in. And every single one of those things was a step I had to overcome, and I think I did it maybe once. So, yeah, for my friend who’s listening or not listening, I’m extremely sorry for that one.

But that is my life, right? Like that’s how I have to go about things, I have to push on this giant risk bubble, and if I push on it enough, it expands! But, its natural state is to wanna shrink, and so, if I let it shrink, then once again, it’s about twice the effort to do it again because I’m already exhausted from doing it the first time.

So, that’s kinda the ‘macro’ part of risk, the ‘micro’ part of risk is a little ridiculous. Once again, I feel very caged by it, I don’t know if everyone with my neurodivergence does, but I am so aware of it, all the time, and it makes me wanna bang my head against my desk. The micro part of it is- You know how people will say people are know-it-alls,right? And like, you correct other people and things like that, and you hear that a lot, and especially about people, once again, with my neurodivergence or with Asperger’s. But the truth, for me at least, is that it’s not about knowing better than everyone else, it’s about not taking the risk of doing it wrong.

So, examples of that: A lot of people in my profession, I’m a tech person, loved to tear things apart when they were little. Like they just- they loved to take things apart, figure out how they worked, and put them together. I couldn’t break things, because there was the risk that breaking the thing would mean I would never be able to put it back together, and if I couldn’t put it back together, I had just destroyed something. And maybe my father would be upset, y’know, maybe it had cost me a lot of money, and so, I couldn’t see how it would be worth it. But on the other hand, if something’s already broken, putting it back together is less risky, right? I guess that doesn’t really go to the whole ‘know-it-all’ thing. Let’s pick a better one.

Grammar police! There we go, that’s a better one. Okay, so, if you are in a class, the class teaches you. So the teacher is the expert, and I’m going to use this term a lot because I think this is how my mind works. The teacher is the expert, and the expert is telling you, straight out, they’re saying, ‘This is how grammar works, this is how English works.’ And because they’re the expert, you can now do it ‘right’, and if you can’t do things right, you get anxious. So the fact that the expert has now taught me this means that I can now do it right, and if somebody isn’t doing it correctly, maybe they need an expert to help them. Which is- I know, it’s funny, but that’s- that’s kind of how it works. So, an expert or somebody teaches you how to do something ‘right’, and then you feel comfortable doing it. If you don’t know how to do something the quote unquote ‘right’ way, then you get really anxious, and you can’t even start sometimes. An example of that is… Heck, even this podcast, y’know, I know some people who can pick up and just start recording. Right? Like they’re just very excited, they start putting things together, they do it wrong, they fail, they start again, they really get into it.

With me, it’s a lot more linear, like, I had to learn how to use my audio software, because I knew I would need audio software. So I can’t start recording until I actually understand how to use this audio software. And then I record a little bit, and then I realize I need music. Well, y’know, in order to do the podcast correctly, I had to figure out where to get music, and I couldn’t create more content until I had the music because it is- Wrong isn’t the word, really, but it’s- it’s like an obstacle like the steps haven’t been met, and so I can’t go ahead and record. It’s so weird, I know. It’s easier when there’s steps, so like- like if you know how to play piano, right? I know how to play piano. I was taught when I was young. I wasn’t really great at it, but I bought myself a keyboard, and I start trying to learn again. And then at some point while I was trying to learn, I realized that my teacher when I was younger, made a big deal about ‘if you don’t raise your wrists correctly, you can hurt yourself, and it’s really hard to unlearn poor form on a keyboard or a piano.’ That realization stopped me, I couldn’t go any further, because I didn’t know if I was doing it the right way, and if I did it the wrong way, then I would have to relearn things. And the worst part about it, is that I know that that’s not necessarily correct? I know there are people out there who bang things out on a keyboard and that’s how they learn, but I can’t, because I was taught by an expert.

And so, you may ask,’Well, how does that change?’ Clearly, now that I’m fifty, I don’t walk around correcting people all the time and telling them they’re wrong. I think a few things change. One is: The rules become broader. So, if I’m talking about this grammar example; I was taught in school, right? That this is how English grammar works, but then I go to college, and I worked for a summer with Steve Pinker, which was amazing, and- and you learn that grammar is innate. And you start to learn that there are rules that are imposed by different cultures on grammar. I mean- the easiest one is that British grammar and US grammar and probably Australian grammar are not exactly the same, but then you learn from, let’s say, one of your minority friends that the grammar for certain minority groups has real rules to it, and has real value behind it, and is a recognized subform of English. And you go, ‘Oh, okay, so there’s other rules, and those rules are just as important as the rules I learned in school.’ So that leads me to have a little more flexibility, because I can now say there’s two right ways, or there’s three right ways, or you learn the regional differences because I’ve lived in so many different states. So you learn- you know, Pittsburgh tends to drop the ‘to be’ or ‘to do’, ‘Something needs to be cleaned.’ as opposed to ‘Something needs cleaned.’ And you expand those rules and you seem a little more flexible, but there’s still rules.

So, how do you get around this? I don’t know that you do. I listen to a lot of classes online if I need to, I fall back on previous rules that I’ve learned. I realized at some point that other people don’t need rules the way I do, which I think was hard. I am probably over analytical, so I’m sure that other people with my issues probably don’t think so hard about all of this, but to me, I don’t like these cages in my brain sometimes. I understand they’re there, I work with them, I know that there are way in which I stand out. And y’know, I’m not here to talk about careers and things like this yet, but I know there are things that I do really well. I know that I am very unique, I know that I bring a lot of positive into things, but sometimes I do rail against my own brain a little bit.

Okay, so, what are the takeaways from this? This first takeaway is: If you struggle like this, it is really a struggle, it is not something that you’re making up, it’s not something that is inherently terrible in of itself, there are ways in which knowing how to do the right thing can save you a lot of time, it can give you a lot of breadth of knowledge, which is where this sort of ‘know-it-all’ thought comes in, and it is truly, a real struggle. For other neurodivergences, so, let me touch on that a little bit and, y’know, mostly this podcast is about me and my brain and trying to explain to you how I interact in the normal world- I live in the normal world. Most people think me a little geeky, but I am perfectly relatable in many ways. But this is what goes on behind the scenes, right? But I want other people to know, and I will have guests at points that will talk to this, I want people to know that things like ADHD affect risk in a different manner, right? As I said at the beginning of the podcast, my son has ADHD, and he will try anything. He has learned in the opposite direction of how I learned, right? So, I had to learn how to expand that risk bubble, I had to learn how to understand that sometimes my brain is making things harder than they need to be. For him, he had to learn that sometimes, the right way is there for a reason. So, he’s one of those people that will touch everything, manipulate everything, his hands are constantly on things- well they were, he’s now in college. But he, y’know, wanted to mix things in the kitchen constantly to see what would happen, and not have a recipe. He just wanted to figure it out. So it’s- it’s a completely different sort of risk thing, coming at it from the opposite direction where, he just sort of, didn’t acknowledge risk as well. And then, as he got older, he started to impose some rules around himself to reduce the risks that he was willing to take. So it’s- it’s a very interesting different direction, that it came from, but it’s still risk, right?

Anyways, I have rambled on very long, and this wasn’t what I expected my first podcast to be about, but with all the issues I had creating the podcast, I realized that this is really what was top of mind for me. You can get past it. It is uncomfortable. It is sometimes a guide rail that you have to follow, and you just have to understand that it’s there, right? So if you know that you are beholden to these rules, then you can do the thing you’re looking to do by making sure that all of your- I’m gonna use a word from work: ‘constraints’, but I guess all of the things that are in the checklist that you need in order to get it done, get done, right? So, knowing it’s there gives you the ability to work with it, to actually get things done, but it is a little bit more jumping through hoops than it might be for other people. And that is the point of this podcast, right? Remember, sometimes, you are jumping through more hoops than other people, and that is okay.

Thank you for tuning in to Memoirs of a Neurodivergent Latina, this podcast was written, edited, and produced by me, Lya Batlle-Rafferty. All music is by Carlos Neda, and this podcast is part of Labrat Solutions Inc.

Episode produced, written, and directed by: Lya Batlle-Rafferty

Music written and performed by: Carlos Neda

Original Header Image by: Gabriel Laberge

Transcription by: Blake Laberge